Did I really mean that? Applying automatic summarisation techniques to formative feedback

D. Field , S. Pulman , N. Van Labeke , D. Whitelock , J. Richardson

Abstract

This paper reports on an application that delivers automated formative feedback designed to help university students improve their assignments. The aim of the system is to improve the confidence and skills of the user by promoting selfdirected learning through metacognition. The system focuses on the content of an essay by using automatic summarisation techniques, automatic structure recognition, diagrams, animations, and interactive exercises that promote reflection. The system is currently undergoing initial exploratory rounds of testing by ex-student volunteers and will be the subject of two full-scale empirical evaluations starting in September 2013. The main claims of this paper are the application and adaptation of graph-based key word and key sentence ranking methods for a novel purpose, and ensuing observations concerning the suitability of two different centrality algorithms for the purposes of key word extraction.

1 Introduction

a fundamental problem in distance education is student attrition, particularly during the early months of enrolment, which appears to be largely due to low morale. graduation rates at distance-learning institutions are often less than 20% (Simpson, 2012). poor retention is evident at the level of individual modules or course units, where completion rates may be as low as 60–70%, or even lower for particular groups of students, such as those from ethnic minorities (richardson, 2012). some students who have dropped out of open university courses have reported that the reason they left was a conviction of their own inadequacy when faced with completing course assignments. these reports are backed up by the drop-out rate that occurs just before the first assignment is due, which, for some courses, is typically as high as 30%.

It appears, then, that there is a need for strategies that increase students’ confidence and skills during the early weeks of enrolment. The ideal strategy would be to provide frequent consultations with human tutors, but resource implications dictate that this is not a viable solution. We therefore decided to build an automated formative feedback system that could provide students with immediate feedback on the quality of their draft assignment essays and reports.

The purpose and design of our system are very different from existing automated assessment systems. The system is primarily focused on user understanding and self-directed learning, rather than on essay improvement, and it engages the user on matters of content, rather than pointing out failings in grammar, style, and structure.

An early prototype of the system (called ‘openEssayist’) is implemented, and is currently undergoing first rounds of user testing. Results from the user testing will inform improvements to the system, which is to be used this September by real university students taking a real Master’s degree module.

2 Background

A number of ‘automated essay scoring’ (AES) or ‘automated writing evaluation’ (AWE) systems exist and some are commercially available (including Criterion (Burstein et al., 2003), Pearson’s WriteToLearn (based on Landauer’s Intelligent Essay Assessor (Landauer et al., 2003) and Summary Street (Franzke and Streeter, 2006), IntelliMetric (Rudner et al., 2006), and LightSIDE (Mayfield and Rosé, 2013)). All these systems now include feedback functionality, though they have their roots in systems designed to attribute a grade to a piece of work. The primary concern of these systems is to help the user make stepwise improvements to a piece of writing. In contrast, the primary concern of our system is to promote self-regulated learning, self-knowledge, and metacognition. Rather than telling the user in detail how to fix the incorrect and poor attributes of her essay, openEssayist encourages the user to reflect on the content of her essay. It uses linguistic technologies, graphics, animations, and interactive exercises to enable the user to compre-hend the content of his/her essay more objectively, and to reflect on whether the essay adequately conveys his/her intended meanings. Writing-Pal (Dai et al., 2011; McNamara et al., 2011) is the system that is most similar to ours in that it aims to improve the user’s skills. Like openEssayist, Writing-Pal also uses interactive exercises to promote understanding. Writing-Pal is very different from openEssayist in terms of its underlying linguistic technologies and the design of its exercises.

The empirical evaluations of openEssayist will focus on users’ perceptions and observations about the system (its usability and its effectiveness), and tutors’ opinions of same (cf (Chen and Cheng, 2008)), rather than on how human-like its marking strategies are (it has none), and we will be carrying out controlled experiments to assess the effectiveness of the system in improving students’ writing proficiency.

There is educational research that argues that using summaries in formative feedback on essays is very helpful for students (Nelson and Schunn, 2009). Ibid concluded that summaries make effective feedback because they are associated with understanding. They found that understanding of the problem concerning some aspect of an essay was the only significant mediator of feedback implementation, whereas understanding of the solution was not (ibid, p. 389). By ‘summaries’ the authors meant both the traditional notion of a short précis, and also some simpler representations, such as lists of key topics. As generating simple summaries falls within the scope of natural language processing (NLP), we decided to use automatic summarisation techniques as the foundation of the linguistic analysis module in the first prototype of the system.

A consequence of the choice to focus on summarisation techniques is that openEssayist is domain-independent, which characteristic also sets openEssayist apart from existing AES/AWEs. This means that it will be possible to quickly apply the system to new domains without the need for manual annotation and machine training of a mass of data from the new domain.

3 Linguistic engine

Our initial approach to producing essay summaries uses two simple extractive summarisation techniques: key phrase extraction and key sentence extraction. Key phrases (as defined in, for example, (Witten et al., 1998)) are individual words and short phrases that are the most suggestive of the content of a discourse. Similarly, key sentences are the sentences that are most suggestive of a text’s content. To identify the key phrases and key sentences of a text, we use unsupervised graph-based ranking methods to calculate the relative importance of words and sentences (following TextRank (Mihalcea and Tarau, 2004) and LexRank (Erkan and Dragomir, 2004)) and select a proportion of the top-ranking items. Before extracting key terms and sentences from the text, the text is automatically pre-processed using four tokenisers, a part-of-speech tagger, and a lemmatiser from the Natural Language Processing Toolkit (NLTK) (Bird et al., 2009). We also remove stop words (articles, prepositions, auxiliary verbs, pronouns, etc.), which are the most frequently occurring in natural language but for our purposes the least interesting [1]. The system also attempts to recognise some structural components.

3.1 Automatic structure recognition

Automatic structure recognition is carried out to ensure that the key word and key sentence analyses are performed on the appropriate data, and to facilitate observations about structure to be used in feedback. Only student-authored sentences are included in the derivation of key phrases and sentences. Non-sentential components like tables of contents, headings, table entries, and captions are also excluded from the calculations, because they are not true sentences and are unsuitable for inclusion in the extractive summary. Some observations about the structure of the essay are used in the feedback, for example, how many of the key sentences are in the introduction and conclusion sections, and how the key words are distributed across the different sections of the essay.

Previous work on automatic essay structure recognition includes by Burstein and Marcu (2003) and Crossley et al. (2011). The former work was concerned with recognising ‘initial’, ‘middle’, and ‘final’ paragraphs, and found that these types of paragraph can be recognised from their linguistic features as automatically identified by Coh-Metrix (Graesser et al., 2004). The latter concerns identifying thesis and conclusion statements in essays using Bayesian classification.

Our own structure recognition is currently achieved through manually-crafted inference rules that have been developed through experimentation with a corpus of 135 university student essays [2]. Each sentence of the essay is labelled according to its role in the essay’s structure. The structural components that the system currently attempts to recognise include the following: title, introduction, discussion, conclusion, heading, figure, bibliography, preface, summary, table of contents, quoted word count, afterword, appendices, sentences quoted from the assignment question.

3.2 Key word extraction

Once each sentence of the essay has been labelled with its structural role, the key words are extracted. The ‘key-ness’ of key words can be thought of as ‘importance’ or ‘significance’. Formally, key-ness aligns with centrality, as in the centrality of a node in a graph. The central-ity of a node tells you, roughly speaking, how strongly connected a particular node is to the whole graph—here, how strongly connected a word is to the whole text. Top-scoring words ranked in this way turn out to be highly suggestive of a text’s content. This has been verified by a formal evaluation carried out by Mihalcea & Tarau (2004).

To compute the words’ key-ness values, each lemma as derived from the essay’s surface form is represented by a node in a graph, co-occurrence relations (specifically, within-sentence word adjacency) are represented by edges in the graph, and a centrality algorithm is used to calculate the key-ness (centrality) score of each lemma. We have experimented with betweenness centrality (Freeman, 1977) and PageRank (Brin and Page, 1998) (see section 5.2).

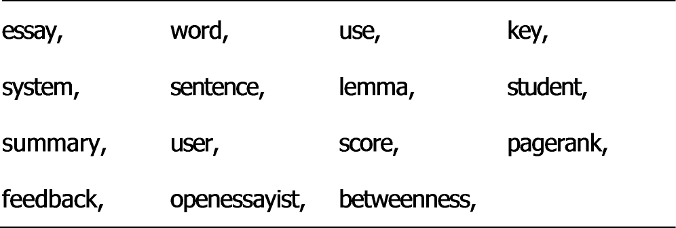

Since a centrality score is attributed to every lemma in the essay, a decision needs to be made as to what proportion of the essay’s lemmas qualify as key lemmas. Using manual observations of the distribution of key lemma scores for all essays, we currently define key lemmas as those in the top 20% of the ranked nodes that have a centrality score of .03 or more. Table 1 shows the key lemmas extracted by the program from the final draft of this paper in descending rank order of centrality (reading from left to right).

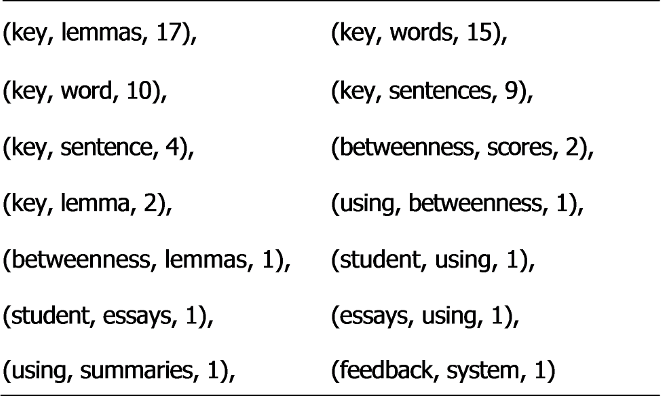

After the key lemmas have been calculated, key phrases are derived by finding within-sentence sequences of key words occurring in the original text. The essay’s key words are the inflections and base forms of the key lemmas, as found in the original surface form. Table 2 shows the bigrams from this paper in descending order of frequency.

3.3 Key sentence extraction

A graph-based ranking method is also used to derive key-ness scores for entire sentences. First, every true sentence (not headings, not captions, not references...) is represented by a node in the graph. Each sentence is then compared to every other sentence and a value is derived representing the semantic similarity of each pair of sentences. The similarity measure we are currently using is cosine similarity, which is a vector space model much used for measuring the similarity of a pair of terms since (Salton et al., 1975). For sentences whose similarity value is greater than 0, the similarity value becomes a weight that attaches to the edge that links the corresponding nodes in the key sentence graph. These ‘edge weights’, are then used in the TextRank algorithm to rank the sentences according to key-ness.

As with key words, no threshold is set by the ranking algorithm to define where in the ranking key-ness ends. Currently we set the number of key sentences to be the top 17 ranked sentences. This value takes into account the mean average number of sentences in the essays in our corpus (65) and the fact that summaries are by definition short.

To illustrate, the top twenty key sentences of this paper as identified by the system have been labelled with sentence-initial superscript numbers (signifying the rank) in parentheses [3].

4 Front end

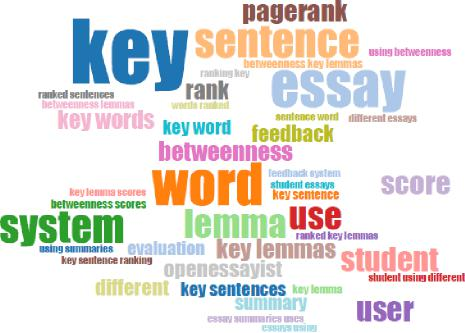

At the front end of the openEssayist system (see (Labeke et al., 2013)), the student pastes her essay into an online form, and a UTF-8-encoded version of the essay is passed to the linguistic engine. This version of the essay preserves the words and the sentence and paragraph structure of the text, but all formatting and graphics are lost. openEssayist analyses the submitted text and presents key words and phrases to the student using different external representations, including a list, a word cloud (see Figure 1 [4]), and a diagram showing their distribution across the essay. Students are invited by the system orchestration to reflect on whether they agree that the key lemmas are representative of the messages they intended their essay to convey, and they are invited to explore the key words by grouping them into themes (using drag-anddrop), and adding new key words. The student’s key sentences are presented to the student in a list. The system orchestration asks whether the student thinks the extracted sentences constitute a good summary of the essay, whether important ideas are missing from the summary, and other questions. A ‘mash-up’ is also presented, in which the student can opt to view key words or key sentences highlighted in context.

5 Informal Evaluation

We have carried out three informal evaluations of the linguistic engine with respect to key word extraction, as follows.

5.1 Predict abstract’s terms from a paper

We evaluated the system on 33 journal papers copied and pasted from an online science journal. We used Journal of the Royal Society Interface and took the January and February 2012 issues, which at the time happened to be the most recent free full issues that could be downloaded [5]. We deliberately chose a very different domain from that of our essay corpus so as to emphasise the non-reliance of the linguistic analysis on any domain-specific information. We used the program exactly as described in this paper, and derived the per-centage of an article’s identified key lemmas that also occurred in the lemmas of the same article’s abstract. (The abstract and the journal-assigned key words for each article were excluded from the derivation of key lemmas.) The range was 31.8% to 82.6%, with a median average of 57.2% and 0.25, 0.5 and .75 quantiles of 50.0%, 59.2% and 65.4% respectively. We were encouraged to find that what we deemed to be good proportions of the identified key lemmas appeared in the ab-stracts.

5.2 Comparison of centrality algorithms

In a second evaluation, we applied the abstracts evaluation described above to comparing the betweenness and PageRank centrality algorithms.

We ran the program on the same set of journal papers, and looked at the results for the top 5, 10 and 20 key lemmas (see Table 3). We observed that betweenness outperformed PageRank, in that it was better at predicting which lemmas would be in a paper’s abstract in all these three cases.

The difference in the scores is small, but its significance becomes clearer when the data is qualitatively examined. Consider, for example, the top 20 PageRank key lemmas (see Table 4) for a paper about cholera and the corresponding betweenness key lemmas (Table 5). The lemma ‘pattern’ occurs in the PageRank top 20 lemmas, but not in the betweenness top 20. In the surface text, ‘pattern’ frequently occurs immediately following ‘mobility’ (8 times). Notably, ‘mobility’ is also a key lemma for both algorithms. Pagerank has promoted ‘pattern’, because ‘mobility’, which is frequently adjacent to ‘pattern’ in the paper, has a high centrality score. In contrast, betweenness does not promote a node’s score if it has a high-scoring neighbour. ‘Pattern’ ranks 16th in the PageRank scores and 32nd in the betweenness scores.

We first noted this promotion in the ranking of a word by its adjacent word in an essay about the Open University. PageRank returned ‘open’ ranked 7th, and betweenness ranked it 26th. In the essay, ‘open’ appeared preceding ‘university’ 22 out of 25 times (88%), Whereas ‘university’ appeared immediately following ‘open’ 15 times out of 24 (62.5%). ‘Open’ has been promoted by the high score of its neighbour ‘university’.

One might think these observations suggest that PageRank would be a better algorithm for identifying key n-grams, whereas betweenness might be better for identifying individual key words. However, the most frequent key bigram according to betweenness is ‘human mobility’ (19 occurrences), which does not appear at all in the PageRank bigrams, owing to the absence of ‘human’ from the PageRank key lemmas. ‘Human’ ranks 34th in the PageRank lemmas, whereas it ranks 10th in the betweenness lemmas.

5.3 Comparison with the null model of random word order

We further examined the difference between Pagerank and betweenness scores by comparing, for one essay, each word’s scores with a null model distribution of scores generated from multiple ‘bootstrapped’ randomised word order versions of the essay. We reasoned, since the key word algorithms rely on word adjacency relations, the randomisations should provide us with an ex-pected distribution of scores independent of word ordering with which to compare key word results. We obtained expected centrality scores for 200 randomised versions, and for the real essay; to determine differences, significance was set at 95%.

In the betweenness results, six of the 30 top-scoring key words had real scores significantly greater than the null model, and none of the real scores was significantly less than the null model. In the PageRank results, three of the 30 top-scoring key words had real scores significantly greater than the null model, but four of the real scores were significantly less. Three of those words occurred in the text adjacent to a word which received a higher PageRank score, and the fourth also had an adjacent key word, though slightly lower-ranking. This experiment, therefore, illustrated by a different method the influence of neighbouring nodes in the PageRank algorithm, and it also raised further suspicions that PageRank might not be the most appropriate centrality algorithm for key word and key phrase extraction.

6 General conclusions

Supervised user testing of the system has recently begun. One user was surprised at the first eight key lemmas identified by the system, saying, “it’s only when we get to ‘education’, [the ninth key lemma] ‘learning’, [tenth. . .] ‘experience’, ‘user’, those are the things that seem a bit more like what I thought it was about”. Key lemma results that surprise the user are invaluable for reflection purposes, as they strongly suggest that the main themes of the text are not the ones the student intended. The same user was also surprised at the system’s decision concerning where the introduction ended. The user was encouraged to reflect on why the system might have misidentified his introduction. He said, “erm, arguably there’s not a very good introduction, maybe it would be the first, erm, like, three paragraphs. It’s certainly not this one here [pointing to the part identified by the system as the introduction]”. He was beginning to consider that a human might also have difficulty recognising his introduction. The user also thought that the 15 key sentences were not representative of his intended messages, and he was disarmed to find only one of the key sentences in the conclusion, explaining that his conclusion expressed the main messages of his essay, and everything that preceded it was building up to a “crescendo” at the end. Clearly the system was provoking the user to reflect on essay characteristics in general, and those of his own essay.

It was clear to observers of the session that using the system helped the student to see what his essay’s main messages were, and to see that his essay was perhaps not conveying the message that he intended. The user reflected more deeply and carefully on the essay as the session progressed. At the end of the session, this user reported that he enjoyed using the system, and said he thought it would be a valuable tool for essay drafting. This user’s reactions were echoed by other users from the testing sessions.

7 Future work

It may be that a different method of key phrase extraction, such as RAKE (Rose et al., 2010), would produce more appropriate results for key n-grams. Roughly speaking, RAKE uses stop words as phrase delimiters, and whole phrases are treated as nodes in the graph, which is quite a different approach from TextRank. In RAKE, however, the score of a node depends on its degree (its immediately neighbouring nodes), so it is more similar to PageRank than betweenness.

We will therefore shortly be carrying out a formal evaluation comparing the performance of betweenness, PageRank, and RAKE with regard to key lemmas, key words, and n-grams of different lengths. As there is a very strong relationship between word frequency and word centrality, we will also be comparing the results with straight frequency counts. The results will inform the design of our prototype. For now, we are using betweenness for key word extraction.

An adaptation we are considering in the key word analysis is to merge key phrases in which the head words are semantically related, e.g., by hyponymy, using WordNet or similar.

We are intending to experiment with alterna-tive sentence similarity measures, including vec-tor space measures of word similarity originally described in (Schütze, 1998).

We intend to add a second dimension to the linguistic engine’s capabilities: to train a classifier to recognise each place in an essay where feedback that falls into a particular category (as proposed by (Nelson and Schunn, 2009)) might be helpful for the student. Then we will employ natural language generation technology informed by research into formative feedback to generate an appropriate feedback comment wherever in-line opportunities for feedback are identified by the system.

We are planning two empirical educational evaluations of openEssayist, which will take place in September 2013 and February 2014, targeting two different Master’s degree modules. The participants will be asked to work on two essays within the openEssayist environment. A third and final essay will be used as a reference point to see if the grades of the students who used openEssayist are higher than for their earlier two essays. Participants will also be encouraged to submit multiple pre-final drafts to the system. We will interview selected participants about their learning experience with openEssayist and we will also obtain judgements from experienced tutors as to the quality of the different essays submitted.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (grant numbers EP/J005959/1 and EP/J005231/1).

References

- Steven Bird, Ewan Klein, and Edward Loper. 2009. Natural Language Processing with Python: Analyzing Text with the Natural Language Toolkit. O’Reilly, Beijing.

- Sergey Brin and Lawrence Page. 1998. The anatomy of a large-scale hypertextual web search engine. In Seventh InternationalWorld-WideWeb Conference (WWW 1998), Brisbane, Australia, April.

- Jill Burstein and Daniel Marcu. 2003. A machine learning approach for identification of thesis and conclusion statements in student essays. Computers and the Humanities, 37(4):455–467.

- Jill Burstein, Martin Chodorow, and Claudia Leacock. 2003. CriterionSM online essay evaluation: An application for automated evaluation of student essays. In J. Riedl and R. Hill, editors, Proceedings of the Fifteenth Conference on Innovative Applications of Artificial Intelligence, pages 3–10, Cambridge, MA. MIT Press.

- Chi-Fen Emily Chen and Wei-Yuan Eugene Cheng. 2008. Beyond the design of automated writing evaluation: Pedagogical practices and perceived learning effectiveness in EFL writing classes. Language Learning and Technology, 12(2):94–112.

- Scott A. Crossley, Kyle Dempsey, and Danielle S. McNamara. 2011. Classifying paragraph types using linguistic features: Is paragraph positioning important? Journal of Writing Research, 3(2):119–143.

- Jianmin Dai, Roxanne B. Raine, Rod D. Roscoe, Zhiqiang Cai, and Danielle S. McNamara. 2011. The Writing-Pal tutoring system: Development and design. Journal of Engineering and Computer In-novations, 2(1):1–11. ISSN 2141-6508 2011 Aca-demic Journals.

- Günes Erkan and R. Radev Dragomir. 2004. LexRank: Graph-based lexical centrality as salience in text summarization. Journal of Artificial Intelligence Research, 22(1):457–479.

- Marita Franzke and Lynn A. Streeter. 2006. Building student summarization, writing and reading comprehension skills with guided practice and automated feedback. White paper, Pearson Knowledge Technologies. Accessed: 14 May, 2013.

- Linton C. Freeman. 1977. A set of measures of centrality based on betweenness. Sociometry, 40:35– 41.

- Arthur C. Graesser, Danielle S. McNamara, Max Louwerse, and Zhiqiang Cai. 2004. Coh-Metrix: Analysis of text on cohesion and language. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, and Computers, 36:193–202.

- Nicolas Van Labeke, Denise Whitelock, Debora Field, Stephen Pulman, and John T. Richardson. 2013. What is my essay really saying? Using extractive summarization to motivate reflection and redrafting. In Proceedings of Formative Feedback in Interactive Learning Environments: A Workshop at the 16th International Conference on Artificial Intelligence in Education (AIED 2013), Memphis, Tennessee, USA, July. To appear.

- Thomas K. Landauer, Darrell Laham, and Peter W. Foltz. 2003. Automatic essay assessment. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy and Practice, 10(3):295–308.

- Elijah Mayfield and Carolyn Penstein Rosé. 2013. LightSIDE: Open source machine learning for text. In Mark D. Shermis and Jill Burstein, editors, Handbook of Automated Essay Assessment Evaluation, pages 124–135. Taylor and Francis.

- Danielle S. McNamara, Roxanne Raine, Rod Roscoe, Scott Crossley, G. Tanner Jackson, Jianmin Dai, Zhiqiang Cai, Adam Renner, Russell Brandon, Jennifer Weston, Kyle Dempsey, Diana Lam, Susan Sullivan, Loel Kim, Vasile Rus, Randy Floyd, Philip McCarthy, and Art Graesser. 2011. The Writing-Pal: Natural language algorithms to support intelligent tutoring on writing strategies. In P.M. McCarthy and Chutima Boonthum-Denecke, editors, Applied Natural Language Processing and Content Analysis: Advances in Identification, Investigation and Resolution, pages 298–311. IGI Global, Hershey, PA.

- Rada Mihalcea and Paul Tarau. 2004. TextRank: Bringing order into texts. In Dekang Lin and Dekai Wu, editors, Proceedings of Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP) 2004, pages 404–411, Barcelona, Spain, July. Association for Computational Linguistics.

- Melissa M. Nelson and Christian D. Schunn. 2009. The nature of feedback: how different types of peer feedback affect writing performance. Instructional Science, 37:375–401.

- John T.E. Richardson. 2012. The attainment of white and ethnic minority students in distance education. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, 37:393–408.

- Stuart Rose, Dave Engel, Nick Cramer, and Wendy Cowley. 2010. Automatic keyword extraction from individual documents. In M.W. Berry and J. Kogan, editors, Text Mining: Applications and Theory, pages 1–20, Chichester. John Wiley and Sons, Ltd. doi: 10.1002/9780470689646.ch1.

- Lawrence M. Rudner, Veronica Garcia, and Catherine Welch. 2006. An evaluation of the IntelliMetricSM essay scoring system. The Journal of Technology, Learning, and Assessment, 4(4).

- Gerard M. Salton, Andrew K. C. Wong, and Chung-Shu Yang. 1975. A vector space model for au-tomatic indexing. Communications of the ACM, 18(11):613–620.

- Hinrich Schütze. 1998. Automatic word sense discrimination. Computational Linguistics, 24(1):97– 123.

- Ormond Simpson. 2012. Supporting students for success in online and distance education. Routledge, London, third edition.

- Ian H. Witten, Gordon W. Paynter, Eibe Frank, Carl Gutwin, and Craig G. Nevill-Manning. 1998. Kea: Practical automatic keyphrase extraction. In Proceedings of the 4Th ACM Conference on Digital Li-braries, pages 254–255.

Notes

- The stop words are removed prior to the construction of the key word and key sentence graphs, but when the key sen¬tences are presented to the student, they look exactly as they appear in the original text.

- These essays were submitted for the same module that will be targeted for a full empirical evaluation of openEssay¬ist in September 2013.

- The actual input .txt file used (converted from the .pdf) and fuller output from the program will be viewable at conference time at: http://www.cs.ox.ac.uk/people/debora. field/did_i_really_mean_that.txt

- The size of the words and phrases is proportional to their frequency.

- http://rsif.royalsocietypublishing.org/content/by/year/2012