OpenEssayist: extractive summarisation and formative assessment of free-text essays

N. Van Labeke , D. Whitelock , D. Field , S. Pulman , J. Richardson

Abstract

OpenEssayist is a system which is currently under development. It aims to provide an effective automated interactive feedback system that yields an acceptable level of support for university students writing summative essays. The principal natural language processing technique currently employed is extractive summarisation using graph-based ranking algorithms. OpenEssayist will be piloted in September 2013 with Open University UK students following a Master’s course of study.

1. INTRODUCTION

Written discourse is a major class of data that learners produce in online environments, arguably the primary class of data that can give us insights into deeper learning and higher order qualities such as critical thinking, argumentation and mastery of complex ideas. These skills are indeed difficult to master as illustrated in the revision of Bloom’s Taxonomy of Educational Objectives (Pickard 2007) and are a distinct requirement for assessment in higher education. Assessment is an important component of Learning and in fact (Rowntree 1987) argues that it is the main driver for learning and so the challenge is to provide an effective automated interactive feedback system that yields an acceptable level of support for university students writing essays. Effective feedback requires that students are assisted to manage their current essay-writing tasks and to support the development of their essay-writing skills through effective self-regulation. Our research involves using state-of-the-art techniques for analysing essays and developing a set of feedback models which will initiate a set of reflective dialogic practices. Our epistemological stance draws on the work of (Bakhtin 1986) where the interpretation of texts is dialogic and that “all thought, including thought inside an individual head, is a dialogue between multiple voices” (Wegerif 2007, p. 17). Promoting this dialogic paradigm is our current route into prompting students’ self-reflection skills, which will address long-standing problems with essay writing.

There are two main components to our automatic essay assessment system. These are (a) the learning analytics engine (EssayAnalyser) and (b) a web application (OpenEssayist) that generates feedback to students in order to help them reflect upon and improve their draft essays. The main pedagogical thrust of e-Assessment of free-text projects is how to provide meaningful “advice for action” (Whitelock 2010) in order to support students writing their summative assessments. It is the combination of incisive learning analytics and meaningful feedback to students which is central to the planning of our empirical studies. These will be carried out at the Open University (OU) by students who will be undertaking a Master’s Degree in Online and Distance Education. Students at the OU receive no support in the drafting of their essays and are returning to formal education after sometimes a 10-year break.

2. e-ASSESSMENT OF FREE TEXT

Although OpenEssayist will not attempt to attribute grades to student essays, the technologies behind the feedback that the system will give are concerned with similar issues to those addressed by automatic assessment systems. In fact, the bulk of work in the automated marking of free text has been concerned with essays. One of the earliest marking systems which was put into commercial use is E-rater (Burstein et al. 2003). E-rater uses various vector-space measures of semantic similarity to determine whether an essay contains the appropriate conceptual content. It also carries out some shallow grammatical processing, and looks for simple rhetorical features (e.g., a paragraph containing a phrase like ‘in conclusion’ ought to go at the end of the essay). While of course it is always possible for a student to ‘game’ such a system (Powers et al. 2002), in practice this does not happen, and E-rater is used routinely as a second marker in the essay component of the US Graduate Management Admissions Test (taken by all candidates for graduate courses in business-related subjects in the US and elsewhere) processing around 0.5 million essays a year.

Other commercial essay marking systems include IntelliMetric (Rudner et al. 2006) and Pearson’s KAT engine, based on Landauer’s Intelligent Essay Assessor (Landauer et al. 2003). Both of these systems use a vector-space technique for measuring semantic similarity to a gold standard essay, known as Latent Semantic Analysis (LSA). For the most part, these systems focus on assessment alone, rather than feedback. Some of the systems can be used in a mode where a draft essay is presented as if it were a final version, thus eliciting a kind of feedback, but the feedback offered is of a standardised kind which is not usually tailored either to the topic or to the individual student, and it typically concentrates on matters of form rather than of content. There are some products which focus on feedback: Summary Street (Franzke & Streeter 2006) is another Pearson product which offers feedback on student summaries of short articles or essays. The underlying technology is again LSA, as it is in Select-A-Kibitzer (Wiemer-Hastings & Graesser 2000), and again feedback tends to be generic. Products which offer individually customised feedback actually are only able to achieve this by using human editors (e.g., Apex [1]).

Thus while automated assessment of free text can be thought of as reasonably well understood (although of course current systems are relatively crude compared to a human marker) the process of constructing individualised feedback automatically is much less so and is the research gap this work wishes to exploit.

3. PROVIDING AUTOMATED FEEDBACK FOR e-LEARNING

Research on feedback itself is extensive, for example with (Hattie & Timperley 2007) reporting on 12 previous meta-analyses which included information on feedback in classrooms and covered 196 studies. Despite the huge number of studies on feedback there is “no consistent pattern of results” (Shute 2008, p. 153). (Kluger & Denisi 1996) argued that the only hope to make sense of the pattern of results was a comprehensive theory, and unfortunately a theory is still lacking. However, various analyses of research results give some guidance as to what – in general – works and we will take that as a starting point. For example, (Nelson & Schunn 2009) in addressing (human generated) feedback connected with essays written by undergraduates taking a history course, examined summarisation, the identification of problems, the provision of solutions, localisation, explanations, scope, praise, and mitigating language as dimensions of feedback. By 'summarisation' they mean both the traditional notion of a short précis, but also some simpler representations such as a list of key topics in an essay. They found that providing summaries of either sort was useful feedback (as measured by improved performance on successive drafts).

Problems can be either global (e.g., ‘you do not provide enough evidence for your arguments’) or local (e.g., ‘this sentence repeats information already given’). Identifying global problems and pointing out whereabouts in the essay a local problem occurs (localisation) were effective feedback strategies. Unexpectedly, providing solutions did not always lead to improvements: identifying incompleteness or providing hints was sometimes helpful, but directly correcting errors could lead to decreases in performance.

The search for ways of generating and delivering effective feedback has been a strong theme throughout the history of technology-enhanced learning. Research on generating feedback from free text, however, has been a relatively minor strand.

The search for ways of generating and delivering effective feedback has been a strong theme throughout the history of technology-enhanced learning. Research on generating feedback from free text, however, has been a relatively minor strand.

4. TOWARDS AN AUTOMATIC ESSAY ASSESSMENT ENGINE

Our objective is to consider whether summarisation techniques could be used to generate formative feedback on free-text essays submitted by students. We decided to start experimenting with two simpler summarisation strategies that could be implemented and tested fairly quickly: key phrase extraction and extractive summarisation. Key phrase extraction aims at identifying which individual words or short phrases are the most suggestive of the content of a discourse, while extractive summarisation is essentially the identification of whole key sentences. Our hypothesis is that the quality and position of key phrases and key sentences within an essay (i.e., relative to the position of its structural components) might give an idea of how complete and well-structured the essay is, and therefore provide a basis for building suitable models of feedback.

The implementation of these summarisation techniques in the learning analytics engine (EssayAnalyser) is based on four main automatic processes: 1) natural language pre-processing of the text; 2) recognition of essay structure; 3) unsupervised extraction of key words and phrases; 4) unsupervised extraction of key sentences. There follows a succinct description of these processes.

Before extracting key terms and sentences from the text, the text is automatically pre-processed using some modules from the Natural Language Processing Toolkit (Bird et al. 2009): several tokenisers, a lemmatiser, a part-of-speech tagger, and a list of stop words. We are experimenting with different approaches to defining a suitable stop word list, and are not yet decided whether to use a domain-independent list or whether to use a domain-specific list derived from appropriate reference materials (using TF-IDF, for example).

The identification of the essay structure is carried out using decision trees developed through manual experimentation with a corpus of 135 student essays submitted in previous years for the same module that the evaluation will be carried out on. The system automatically recognises which structural role is played by each paragraph in the essay (including summary, introduction, conclusion, main body, references, etc.). This identification is achieved regardless of the presence of content-specific headings and without getting clues from formatting mark-up. We have not yet carried out a formal evaluation of the structure identification procedure, but its accuracy rates are good enough to use in first rounds of OpenEssayist testing, and are continually improving.

Essay Analyser uses graph-based ranking methods to perform unsupervised extractive summarisation, following TextRank (Mihalcea & Tarau 2004, 2005). One graph is used to derive key words and short phrases, and a second graph is used for the derivation of key sentences. Regarding key words, to compute a 'key-ness' value for each word in the essay, each unique word [2] is represented by a node in the graph, and co-occurrence relations (specifically, within-sentence word adjacency) are represented by edges in the graph. 'Key-ness' can be understood as 'significance within the context of the essay'. A centrality algorithm – we have experimented with betweenness centrality (Freeman 1977) and PageRank (Brin & Page 1998) – is used to calculate the significance of each word. Roughly speaking, a word with a high centrality score is a word that sits adjacent to many other unique words which sit adjacent to many other unique words which…, and so on. The words with high centrality scores are the key words. Since a centrality score is attributed to every unique word in the essay, a decision needs to be made as to what proportion of the essay's words qualify as key words. The key word distribution of scores follows the same shape for all essays, an acute elbow and then a very long tail, observed for word adjacency graphs by (Ferrer i Cancho & Solé 2001). We therefore currently take the key-ness threshold to be the place where the elbow bend appears by eye to be sharpest. We are investigating alternative and less subjective methods of deciding where the threshold should be (e.g., investigating graph structure through randomisation methods). Once key words have been identified, the system matches sequences of these against the surface text to identify within-sentence key phrases (bigrams, trigrams and quadgrams).

A similar graph-based ranking approach is used to compute key-ness scores to rank the essay's sentences. Instead of word adjacency (as in the key word graph), co-occurrence of words across pairs of sentences is the relation used to construct the graph. More specifically, we currently use cosine similarity to derive a similarity score for every pair of sentences. The similarity scores become edge weights in the graph, while whole sentences become the nodes. The TextRank key sentence algorithm (based on PageRank but with added edge weights) is then applied. We are intending to experiment with alternative similarity measures, including vector space measures of word similarity originally described in (Schütze 1998).

Our task is now to look for ways of exploiting these results and devise suitable models of feedback.

5. OPENESSAYIST: CURRENT AND FUTURE WORK

The design of the first version of the system has focused on defining the essay analytics engine and integrating it into a working web application (called OpenEssayist) that supports draft submission, analysis and reporting.

At the front-end level, the instructional interactions have been deliberately limited to fairly unconstrained forms, leading the system toward a more “explore and discover” environment. Our aim was to establish a space where emerging properties of the interventions being under investigation (i.e. using summarisation technique for generating formative feedback) could be discovered, explored and integrated into the design cycles in a systematic way, contributing to both the end-product of the design cycle (the system itself) and to its theoretical foundations.

Several external representations are being designed, reporting the different elements described above in different ways, trying to highlight such properties on the current essay (or, on changes over successive drafts).

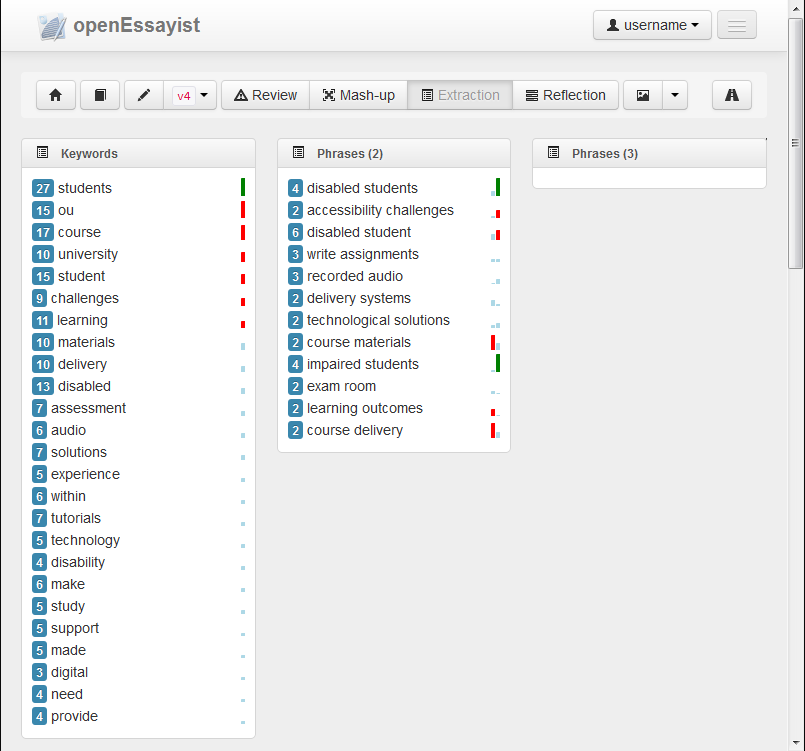

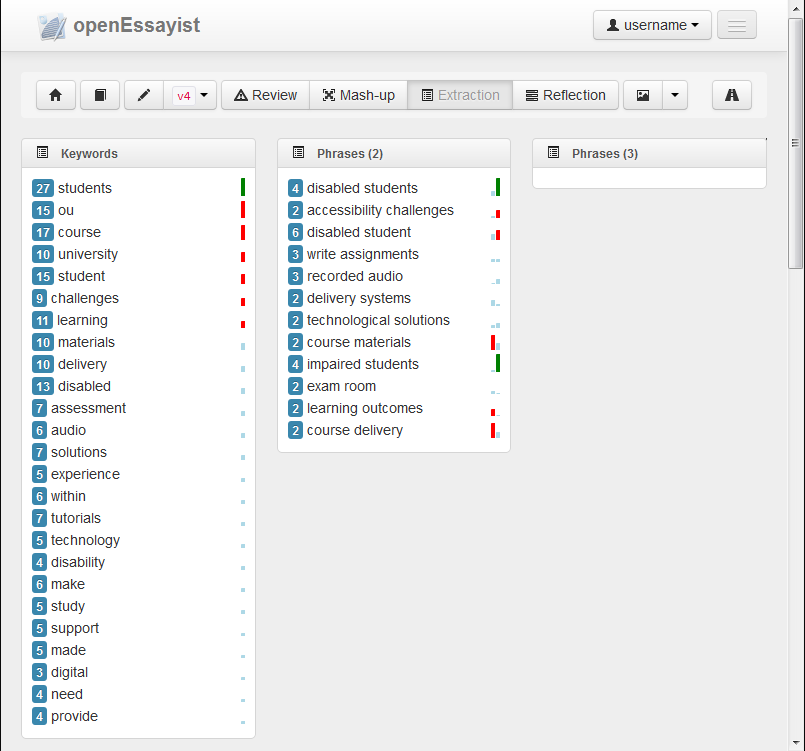

For example, key words and key phrases can be explored on their own, by simple lists of ranked terms (Figure 1) of by dispersions graphs.

Figure 1

Key word and key phrase extraction in OpenEssayist, with the key words (left) and bigrams (right) ranked by their centrality score. The leading number indicates the frequency count of the term in the surface text; the sparklines indicate the centrality score(s) of the key word(s).

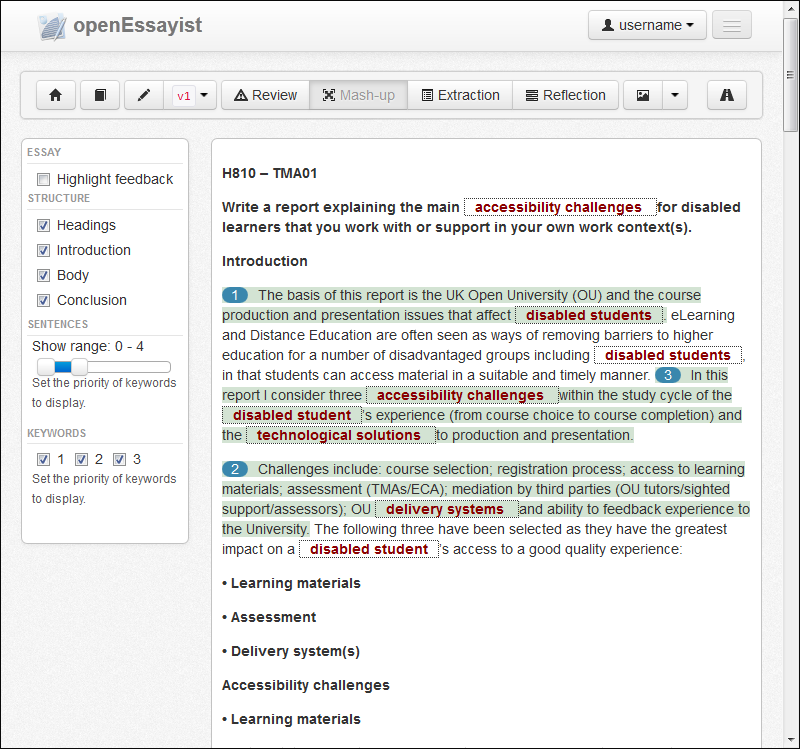

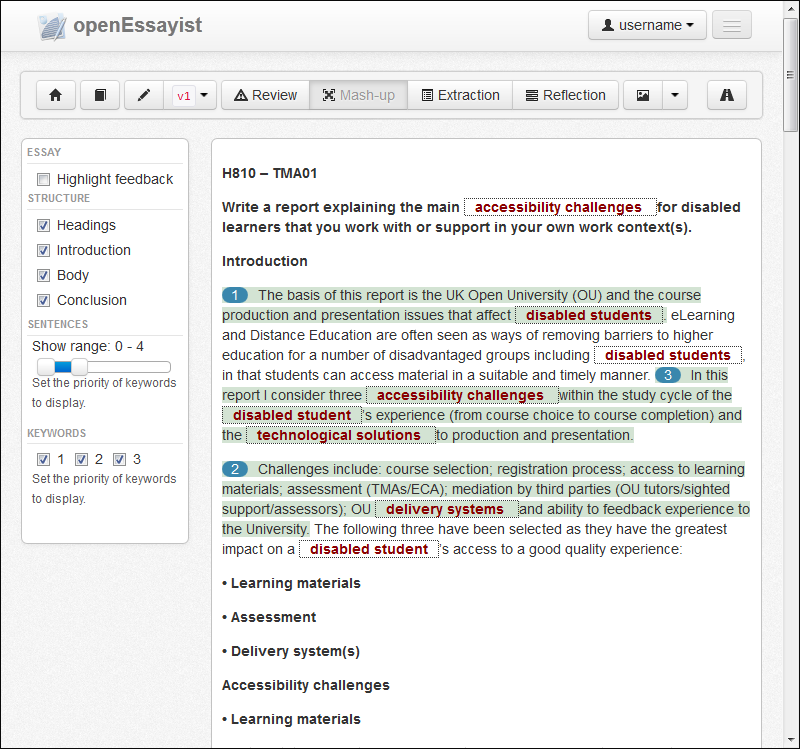

Conversely, more holistic approaches are being tried by designing “mash-ups” where keywords and key sentences are highlighted in context in the essay itself (Figure 2), helping students to investigate the distribution of keywords across their essay, including potential implications (e.g. pondering the scarcity of keywords in certain parts of the essay such as the introduction or conclusion). Both figures are generated out of a real essay submitted on one of our target course, entitled “Accessible online learning supporting disabled students” (H810, a postgraduate module in Online and Distance Education; the assignment question can be seen on top of the text in Figure 2).

Figure 2

A snapshot of the interface of OpenEssayist, showing key words and phrases displayed in the essay context. Sentences in light-grey (green) background are key sentences as extracted by EssayAnalyser (the number at the start of the sentence indicates its ranking); bigrams are indicated in bold (red) and boxed.

In that sense, the current version of the prototype has adopted a data-centric point of view: elements are being put in place, tested, and redesigned to explore content and conditions for user interventions and system support.

Our work is now focusing on three parallel but inter-connected lines of experimentations: 1) improve the different aspects of the essay analyser (e.g. try out different “key-ness” metrics, introduce domain-specific lists of stop-words); 2) design further analyses (e.g. factor analysis) to run on our corpus of essays (5 years of essays on the H810 course, all marked and annotated by human tutors), to identify trends and markers that could be used as progress and/or performance indicators; 3) undertake a program of iterative, user-centred, design and testing of the system, to refine possible usage scenarios, test pedagogical hypotheses and models of feedback.

The second phase of the design of OpenEssayist will rely on these experimentations to inform the models that will then be evaluated in September 2013 by a new cohort of students on the H810 module. The system will therefore be used in an authentic e-learning context.

This project which is in its infancy is emerging at the inter-section of research into learning dynamics, deliberation platforms and computational linguistics. Our current major challenge is to generate information displays that will assist learners and tutors to understand where support intervention such as “advice for action” will improve the discourse for learning.

6. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC, grant numbers EP/J005959/1 & EP/J005231/1).

7. REFERENCES

- Bakhtin, M. M. (1986). Speech Genres & Other Late Essays. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press.

- Bird, S., Klein, E., and Loper, E. (2009). Natural Language Processing with Python. Cambridge, MA: O’Reilly Media, Inc.

- Brin, S., and Page, L. (1998). The anatomy of a large-scale hypertextual Web search engine. Computer Networks and ISDN Systems 30(1), pp. 107–117.

- Burstein, J. C., Chodorow, M., and Leacock, C. (2003). Criterion(SM) Online Essay Evaluation: An Application for Automated Evaluation of Student Essays. In Proceedings of the Fifteenth Conference on Innovative Applications of Artificial Intelligence, Acapulco, Mexico pp. 3–10.

- Ferrer i Cancho, R., and Solé, R. V. (2001). The small world of human language. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences 268(1482), pp. 2261–2265.

- Franzke, M., and Streeter, L. A. (2006). Building student summarization, writing and reading comprehension skills with guided practice and automated feedback. Highlights from Research at the University of Colorado. Boulder, CO: Pearson Knowledge Technologies.

- Freeman, L. C. (1977). A set of measures of centrality based on betweenness. Sociometry 40(1), pp. 35–41.

- Hattie, J., and Timperley, H. (2007). The Power of Feedback. Review of Educational Research 77(1), pp. 81–112.

- Kluger, A., and Denisi, A. (1996). The effects of feedback interventions on performance: A historical review, a meta-analysis, and a preliminary feedback intervention theory. Psychological Bulletin 119(2), pp. 254–284.

- Landauer, T. K., Laham, D., and Foltz, P. (2003). Automatic Essay Assessment. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice 10(3), pp. 295–308.

- Mihalcea, R., and Tarau, P. (2004). TextRank: Bringing order into texts. In Proceedings of Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP) 2004, Spain pp. 404–411.

- Mihalcea, R., and Tarau, P. (2005). A language independent algorithm for single and multiple document summarization. In Proceedings of the International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (IJCNLP), pp. 19–24.

- Nelson, M. M., and Schunn, C. D. (2009). The nature of feedback: how different types of peer feedback affect writing performance. Instructional Science 37(4), pp. 375–401.

- Pickard, M. J. (2007). The new Bloom’s taxonomy: An overview for family and consumer sciences. Journal of Family and Consumer Sciences Education 25(1), pp. 45–55.

- Powers, D. E., Burstein, J. C., Chodorow, M., Fowles, M. E., and Kukich, K. (2002). Stumping e-rater: challenging the validity of automated essay scoring. Computers in Human Behavior 18(2), pp. 103–134.

- Rowntree, D. (1987). Assessing Students: How Shall We Know Them? London: Kogan Page.

- Rudner, L. M., Garcia, V., and Welch, C. (2006). An Evaluation of IntelliMetricTM Essay Scoring System. The Journal of Technology, Learning and Assessment 4(4).

- Schütze, H. (1998). Automatic Word Sense Discrimination. Journal of Computational Linguistics 24(1), pp. 97–123.

- Shute, V. J. (2008). Focus on Formative Feedback. Review of Educational Research 78(1), pp. 153–189.

- Wegerif, R. (2007). Dialogic education and technology: Expanding the space of learning. New York: Springer.

- Whitelock, D. (2010). Activating Assessment for Learning: Are We on the Way with Web 2.0? In Web 2.0-Based E-Learning: Applying Social Informatics for Tertiary Teaching, eds. Mark J.W. Lee and Catherine McLoughlin. Hershey, PA: IGI Global pp. 319–342.

- Wiemer-Hastings, P., and Graesser, A. C. (2000). Select-a-Kibitzer: A computer tool that gives meaningful feedback on student compositions. Interactive learning environments 8(2), pp. 149–169.

Notes

- Apex, http://www.apexwriters.com/free-essay-editing.jsp.

- In fact the graph nodes are the lemmas of the unique words, but for brevity's sake, we will speak in terms of words.