Using student experience to inform the design of an automated feedback system for essay answers

B. Alden , N. Van Labeke , D. Field , S. Pulman , J. Richardson , D. Whitelock

Abstract

The SAFeSEA project (Supportive Automated Feedback for Short Essay Answers) aims to develop an automated feedback system to support university students as they write summative essays. Empirical studies carried out in the initial phase of the system’s development illuminated students’ approaches to and understandings of the essay-writing process. Findings from these studies suggested that, regardless of their experience of higher education, students consider essay writing as: 1) a sequential set of activities, 2) a process that is enhanced through particular sources of support and 3) a skill that requires the development of personal strategies. Further data collected from tutors offered insight into the feedback and reflection stages of essay writing. These perspectives offer important considerations for the ongoing, iterative development of this automated feedback system and indeed, for any institution developing tools to support students’ writing.

Introduction

OpenEssayist is an automated, interactive feedback system designed to provide an acceptable level of support for students as they write essays for summative assessment. There are two main components to the system: 1) the learning analytics engine and 2) the web application that generates feedback for students (OpenEssayist) (Van Labeke et al., 2013a ; 2013b). The rationale for building such a system rests largely on the knowledge that essay-writing is a challenging task for many students. Skills such as critical thinking, argumentation and working with complex concepts—all fundamental learning outcomes in higher education—are frequently demonstrated and assessed in the form of written essays. Yet, the development of these skills is a slow and difficult process because it requires writers to “proceduralize knowledge at multiple cognitive, metacognitive and linguistic levels” (Bruning et al., 2013, p. 25). Some evidence suggests that students find the essay-writing experience emotionally difficult as well (Tickle, 2011 ).

OpenEssayist aims to support students during the essay-writing process by analysing drafts of students’ essays and instantaneously offering automatic, individualised feedback or “advice for action” (Whitelock, 2010). Students can use feedback from the system to develop their essay-writing skills through self-regulation and the iterative use of the system.

In order to inform the initial development of OpenEssayist, it was important to gain a better understanding of students’ approaches to and understandings of the essay-writing process. Fundamentally speaking, the efficacy of this software will rely on understanding the answers to two questions: 1) How do university students go about writing essays? and 2) In what ways can OpenEssayist support university students as they write essays? This paper reports on empirical research that was carried out to address these questions.

Students’ experiences of essay-writing

The initial design and development of OpenEssayist required an insight into the nuts and bolts of the essay-writing process. How do students prepare for and plan their writing? How do they draft their work? How do they prepare a final draft? A quick internet search yields countless pages of links to guidance for effective essay-writing. It is clear there is insight into what students need to support their essay-writing skills. It is unclear how much of this insight has come from a second-order perspective (i.e. the students’) or whether this wealth of advice is derived from an instructional viewpoint. While the design of OpenEssayist is largely shaped by pedagogical theory, it was considered worthwhile to understand the writing process through students’ firsthand accounts.

There are at least two studies that are highly relevant to this empirical strand of OpenEssayist’s development. Chandrasegaran, Ellis and Poedjosoedarmo (2005) carried out usability trials with students to aid the development of Essay Assist—a computer program for guiding students towards appropriate decisions in the essay-writing process. The design of Essay Assist was informed by theoretical frameworks related to a sociocognitive view of writing. In this sense, the activity of writing is embedded in a particular social context. Essay Assist helps students make context-specific decisions about their essay (e.g. to understand the teacher’s requirement for the task, to analyse the essay’s audience, etc.). Participants in their study worked through the software prototype and offered comments as to what they thought were helpful features of the program and what were its shortcomings.

Roscoe et al. (in press) carried out a multiple-method usability study to refine and further develop The Writing Pal (W-Pal). W-Pal is an intelligent tutoring system designed to improve students’ writing skills using a combination of strategy instruction, game-based practice, essay-writing practice and automated formative feedback. Although the design of W-Pal was informed by strategy theory and writing pedagogy, the initial stages of development were also shaped by focus group research with teachers. Subsequent usability testing of the W-Pal prototype involved students.

These two studies offer relevant examples of how input from key stakeholders informed the development of automated tools for enhancing writing skills. However, neither of these studies elicited input from students in the early design stages. This project (OpenEssayist), on the other hand, wanted to capture these key data so that the students’ perspectives could be viewed alongside relevant theory.

The studies

Focus groups were carried out with two samples of students at the UK’s Open University. The first focus group was labelled ‘Novice Learners’ and comprised students who were enrolled on a foundation level undergraduate module in Social Science. For all of the participants in the Novice Learners group, this module was their first experience of studying in higher education. Choosing to sample students on this particular module ensured the participants would have completed and received feedback on at least one tutor marked assignment at the time of the research and that this assignment would have been in the form of a written essay.

The second focus group was labelled ‘Experienced Learners’ and included university students who had taken several Arts or Social Science modules previously. The rationale for sampling from new and experienced learners was to capture a range of students’ experiences of essay-writing that could possibly inform the design of OpenEssayist. Grouping participants by their level of experience maintained the homogeneity of the groups, offering the participants an opportunity to relate to shared experiences and common features of study at particular levels.

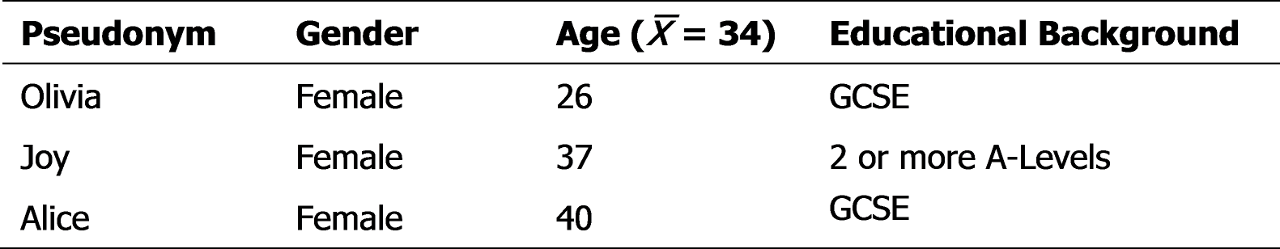

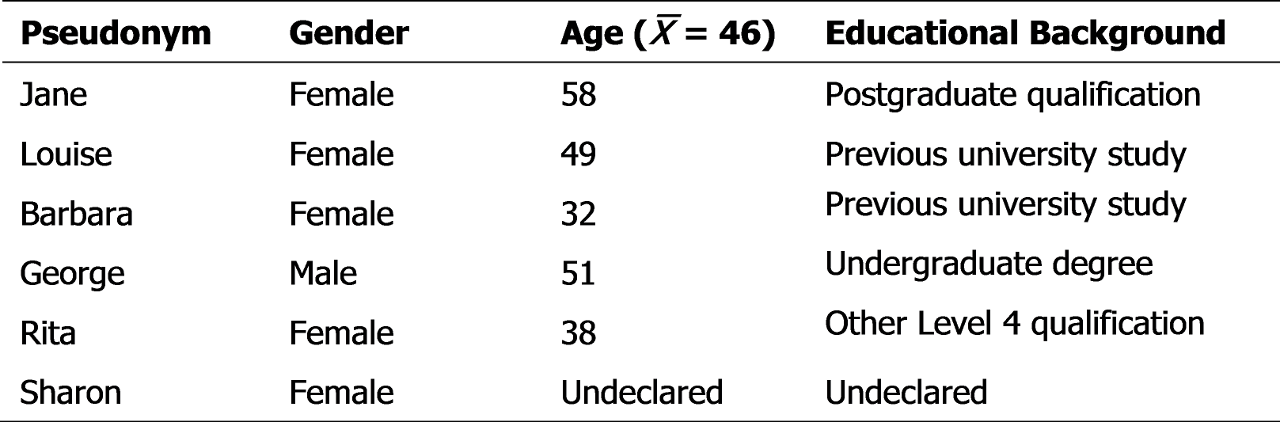

Three participants were in the Novice Learners group and six were in the Experienced Learners group. These samples sizes are characteristic of “mini-focus groups”, which offer the participants more opportunities to share their ideas but may limit the overall pool of ideas (Krueger, 1994). Although a greater sample size was anticipated for the Novice Learner group, the data elicited from both groups were very rich and were therefore deemed a valid contribution to this research. Table 1 and Table 2 show the demographic profile of each group. Pseudonyms have been used instead of real names.

Table 2

Demographic profile of Experienced Learners (N=6).

Each focus group lasted for approximately one hour and used a thematic approach to questioning. This allowed the moderator to probe participants’ experiences of essaywriting within a set of topics (Morgan, 1988). For both focus groups, these topics included: access to support, planning, drafting and feedback.

Data from the focus groups were recorded and transcribed. Thematic inductive analysis was carried out to identify emerging categories (Braun & Clarke, 2006).

Findings

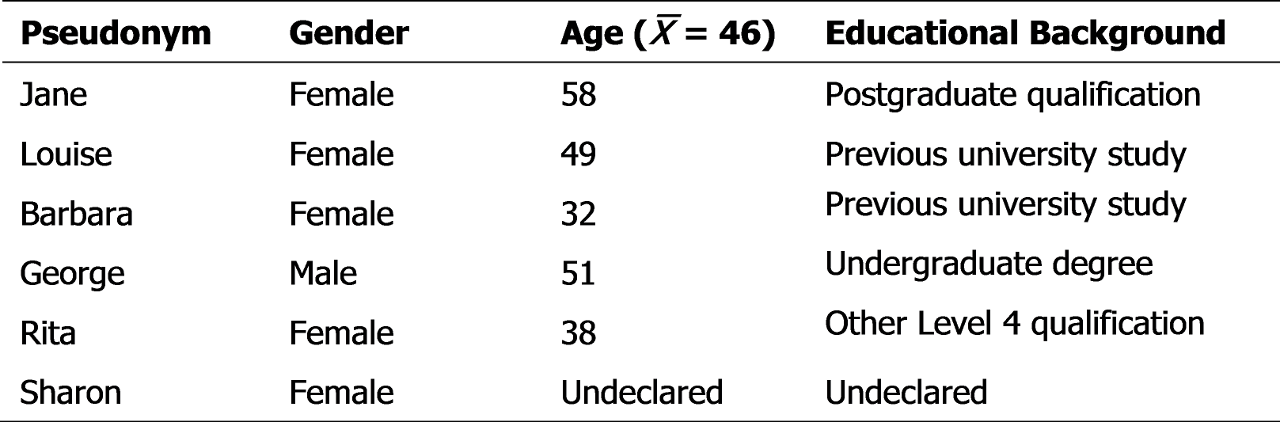

Findings from these focus groups suggested that, regardless of their experience of higher education, students consider essay-writing as: 1) a sequential set of activities, 2) a process that is enhanced through particular sources of support and 3) a skill that requires the development of personal strategies. Findings also suggested that students with more experience of higher education may have different expectations of the essay-writing process than students with less experience.

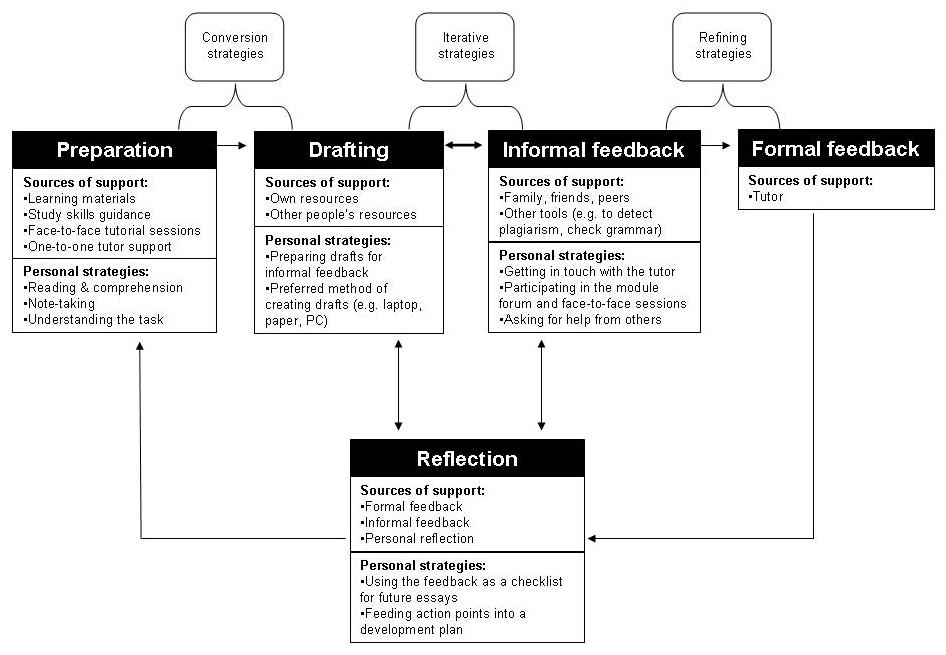

Participants in both focus groups related to essay-writing as a five-stage process that loops into future iterations. These stages can be summarised as: 1) preparation, 2) drafting, 3) informal feedback, 4) formal feedback and 5) reflection. The preparation stage involves sub-activities such as reading, note-taking and planning, although the participants approached these tasks in different ways. It was clear that the participants each had personal strategies for dealing with this stage of writing:

“I have to do a brainstorm. You know, like a spider graph. You know, the different ideas that are coming out of here, in terms of what I’ve read.” (Joy)

“I use post-its and highlighting, really. I find it works for me.” (Olivia)

“I read everything until I’m sure that I’ve understood, even if it means leaving it to the last minute to start writing it.” (Rita)

The drafting stage involves conversion strategies for transforming a rough plan to a first draft and then reworking that draft into a final version. Again, there was no common approach to creating drafts but the main concerns included: finding the right words, using the key terms correctly, and making sure the writing flows. Each participant had personal strategies for addressing these issues:

“I’ll print it out and read it, see if it flows. Then, I’ll correct it on the computer, read that and see what I think. The thing I really struggle with is that each paragraph flows from one to the next.” (Joy)

“Initially, I handwrite it, then I type it up, edit it. It’s a long process.” (Barbara)

“I do a terminology box with all the words we should be using. I find myself keeping checking that and see what words I need to use.” (Olivia)

“It’s so hard to find the right words.” (Louise)

Interestingly, the Novice Learners had several strategies for getting informal feedback from family and friends. They also valued feedback from their peers during face-to-face tutorials:

“My husband hasn’t done a degree but my father in law has so I’ve been picking his mind. Because he’s been through that.” (Alice)

“When I come to these groups it’s really nice to have some feedback from other students.” (Olivia)

Using informal feedback to improve their drafts involved certain iterative strategies:

“But, when I’m happy with it, that’s when I’ll give it to my mum and she’ll make corrections. Then, the final one’s done. It takes far too long.” (Joy)

Participants in the Experienced Learners group did not access sources of support such as family, friends and peers but this was generally due to a lack of time and not knowing anyone who had specialist knowledge on the essay topic:

“I’ve never shared mine purely for time and because of the subject area.” (Sharon)

“When I was doing the postgrad, I didn’t show it to anyone but that was more to do with the subject matter.” (Jane)

Across both groups, two participants mentioned that they used free online tools to check their work for plagiarism. When probed about other online tools they might use when writing an essay, they were not aware of any others:

“I also used, I uploaded my assignment, I just googled online, in terms of plagiarism, and uploaded it. It was online. I just uploaded it to see if I’d copied a sentence. It just came back, and it was good.” (Joy)

“One of my friends told me about this website where you submit your assignment and then it highlights blocks of plagiarism.” (Rita)

Participants acknowledged another stage in the essay-writing process that involved receiving formal feedback on their final draft from their tutor. Personal strategies and sources of support for this stage were not made explicit by the participants. However, certain refining strategies were implied in many of their comments about the previous stage. The main theme that emerged on this topic had to do with receiving feedback:

“I think it’s quite important to make mistakes. That’s why the feedback is so important. There’s quite a lot of support there.” (Olivia)

“Um, I was really pleased with the feedback I got from my tutor. It was very constructive. I have put too much in my introduction. I wasn’t concise enough. I put too much in my conclusion because I tried to put everything else there.” (Joy)

[Writing essays is] “Challenging, interesting, exciting, getting that result back from your tutor.” (Alice)

A final stage in the essay-writing sequence involved reflection on the feedback. Participants talked about strategies for using the tutors’ comments to develop their writing skills. Indeed, most of these participants indicated that reflection played a role at each stage of the process:

“The feedback that I’ve got, I’ll write it down and make sure it goes into the next one. I don’t want to make the same mistakes twice. If I make new mistakes that is fine.” (Joy)

Figure 1 summarises the findings of these studies by representing these five stages of the essay-writing process. This flow chart also includes the inter-stage strategies (i.e. converting notes to drafts; the iterative revising of drafts and refining the final draft) that are suggested above.

Figure 1

Flow chart depicting the stages of essay-writing derived from these studies.

Constraining factors

Both groups highlighted several constraining factors at each stage of the essay-writing process. Some of these factors had to do with technology. For example, Olivia did not have a computer, so had to use her mobile phone to access the module website. Joy found sitting in front of a computer a “huge distraction”, so decided to write her drafts on paper. Sometimes there were barriers to writing the essays when students’ preferred learning strategies could not be used. For example, Louise and Jane had both relied on having the printed Assessment Guide to hand as they wrote their essays. When this resource was only made available online, they found the extra step of downloading and printing the Guide a nuisance. Jane also said that even though she has a personal strategy of writing down the references as she takes notes, she explained that sometimes she forgets and spends a lot of time having to “go back and look”.

Some of the participants expressed their feelings about the word limit of the essay being a constraint. Sharon shared an experience of when her tutor said she should have talked about “x, y and z”. And, even though she originally included “x, y and z”, she had to omit it on the final draft due to the word limit. Other factors that affect the essay-writing process include having unsupportive tutors and not having access to informal sources of support (i.e. friends, family and peers). The most commonly cited hindrance to the essaywriting process was poor time-management.

Inter-group differences

The main difference between the two groups was that the Experienced Learners had clearer expectations of the essay-writing experience. Participants in this group perceived essay-writing at higher levels of study to involve different approaches to writing. They had a greater awareness of the marking criteria against which the tutors mark and provide feedback on essays. Participants in this group expected feedback at higher levels of study to focus on “things that have been done well” (Jane), while at the same time be tailored to help individual students (Sharon).

There was a difference of opinion among the Experienced Learners as to whether there should be more tutor support at higher levels or at lower levels of study. And, although a consensus was never reached, the group seemed to agree that at least the tutor support would be different at different levels. It was evident that the Experienced Learners had a greater contextual awareness in the sense that they were more familiar with the University’s systems. This group talked more easily about their ideas for supporting students’ writing but had to be prompted to talk about their own experiences of essaywriting. Many of their ideas were based on developing a community of practice around essay-writing. These ideas included: 1) sharing examples of best practice, 2) implementing a peer support scheme for essay-writing, 3) doing more reflective activities, 4) having more opportunities to write unmarked essays and 5) having the same tutor as a mentor across several modules.

Tutors’ perspectives

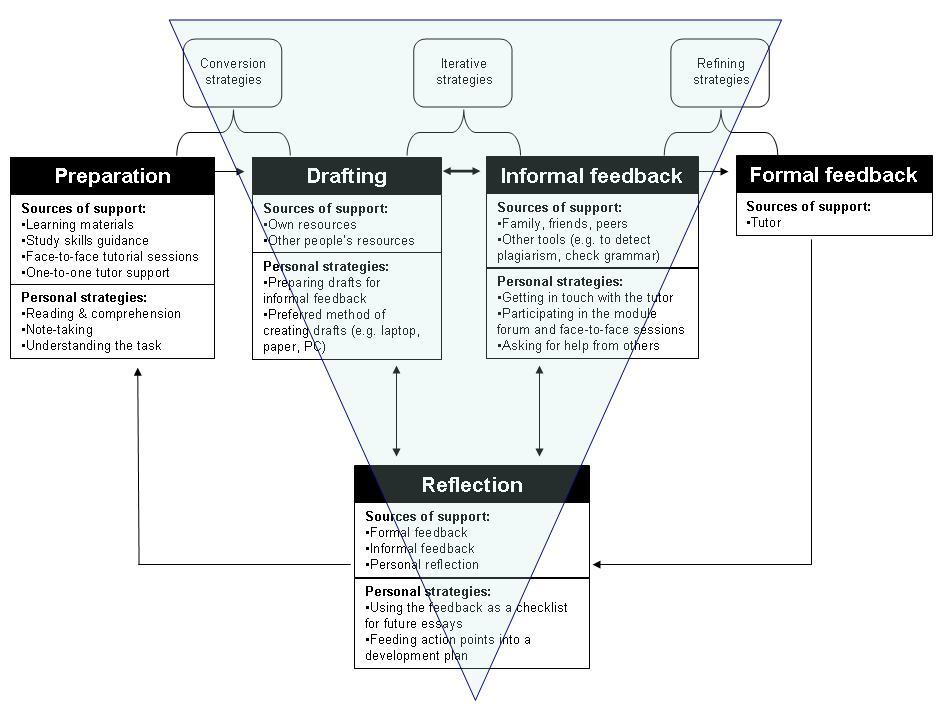

From the literature review that was carried out for these studies, it was clear that tutors were a rich source of data regarding students’ experiences of essay-writing. Also, when looking at Figure 1, it seemed there might be more to be discovered from the tutors about the formal feedback stage. Following the student focus groups, expert interviews with two distance tutors from a postgraduate module at The Open University were carried out to explore some of the meta-tasks around the feedback stages.

The tutors in this part of the study both perceived their role as a facilitative and supportive one. They commented that their job was to help students “step up” to the next assessment (essay). Contrary to the input from the student focus groups, these tutors confirmed that they also support students during the informal feedback stage. This happens as students email sections of their drafts to the tutors for comment. Often, tutors are asked to comment on the level of detail and the essay structure before students submit their essay for formal feedback. This discursive and iterative use of tutors as sources of support during the drafting stages seems to happen among the stronger students. Both tutors perceived OpenEssayist as a tool that might be able to “catch the ones who need support”.

When providing formal feedback, both tutors noted that they use a repertoire of stock phrases to highlight strengths and weaknesses and to give ideas for improving future work. The tutors were not always sure about how students feel about the feedback because “reflective emails rarely come through”. However, they noted that this evidence usually comes from seeing visible improvements on future essays.

The tutors expressed the potential of OpenEssayist to support students in the reflective stages of essay-writing. One idea was that a learning program could be designed around system’s output to their own expectations. When submitting subsequent drafts, such a learning program could elicit critical thinking by asking students to identify the key differences between the drafts.

Similarly to the Experienced Learners group, these tutors saw the opportunity for OpenEssayist to facilitate a supportive community. One tutor explained that a system like this one should not work in isolation but should work as part of a bundle of support offered from the tutor and the peer group.

The tutors suggested that while OpenEssayist should complement the functions of the tutor, it needed to be “risk-managed”. More specifically, the tutors explained that the system should not: 1) stifle a student’s creativity, 2) contradict the feedback from the tutor, 3) offer machine-generated praise, 4) produce overly negative comments or 5) offer a score. The tutors said that students need to be aware that OpenEssayist is merely a tool and, as such, it requires the user’s critical evaluation of its output. These tutors believed that students should be limited to a certain number of drafts when using the system and ideally be encouraged to reflect on the output.

Discussion

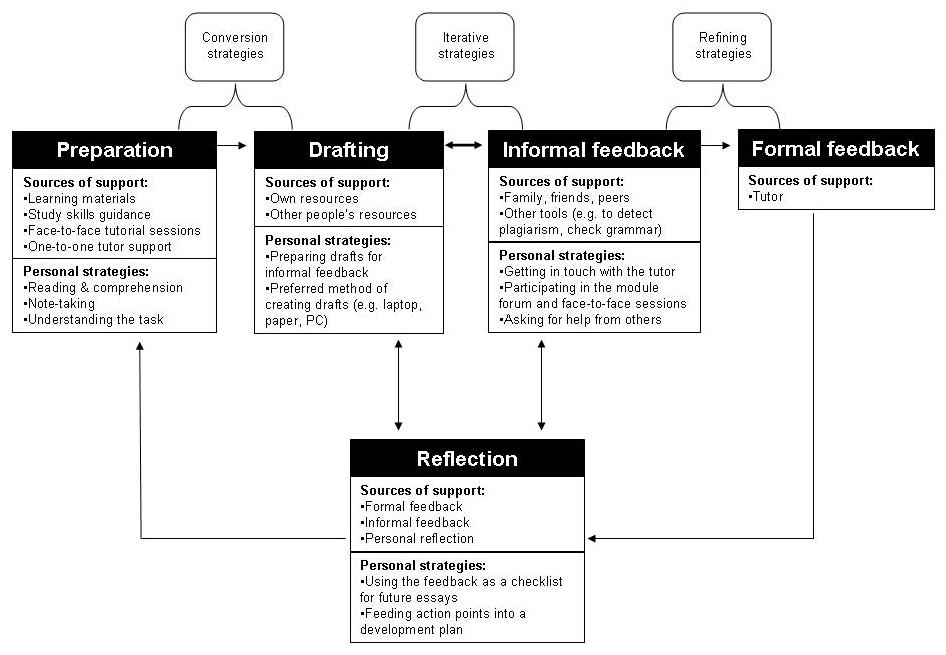

OpenEssayist aims to support students by offering automated feedback on drafts of their essays before they submit their work to be formally assessed by the tutor. Figure 2 shows the obvious overlap of OpenEssayist’s functions and the stages of essay-writing. However, it is germane to consider ways of supporting student writers at each stage of the process, especially in developing reflective, metacognitive skills. Therefore, a key question for the design of the system is one of scope. What is the remit of support that OpenEssayist can effectively provide?

Figure 2

Stages of essay-writing showing the obvious scope (shaded triangle) of OpenEssayist in supporting the writing process.

Another key question involves risk. How can OpenEssayist be risk-managed? A suggestion from the empirical research offered the idea of embedding the system in a reflective, developmental program. This may offer ways for OpenEssayist to be used in a fairly structured and monitored way. By encouraging students to provide reflective comments before and after using the system, the risk of a mismatch between output and expectations could be tempered.

A third question for the design of the system is one of community. A key theme among the Experienced Learners and the tutors was one of developing a community of practice to support essay-writing. Could a system such as this one be the hub of this community? Could OpenEssayist open routes for sharing best practice, giving and receiving peer feedback, mentoring and developing reflective skills?

The next stage

The empirical research that is reported here aimed to address two questions: 1) How do university students go about writing essays? and 2) In what ways can OpenEssayist support university students as they write essays? Figure 1 and Figure 2 go some way in representing answers to these questions. However, more consideration needs to be given to identifying opportunities for using OpenEssayist to support students’ writing.

Presently, a prototype has been developed to explore content and conditions for user intervention and system support. The next stages of development include: 1) refining and further developing the linguistic engine, the feedback strategies and the user interface of OpenEssayist, 2) designing further analyses to identify trends and progress markers in student essay-writing and 3) undertaking a programme of iterative, user-centred design and testing of the system. The aim of this last stage is to refine possible usage scenarios, test pedagogical hypotheses and establish models of feedback.

The second phase of design for OpenEssayist will rely on these empirical studies to inform the prototype that will then be evaluated in September 2013 by a new cohort of university students.

Acknowledgements

The SAFeSEA project team is particularly grateful to The Open University students who participated in this study and the Arts and Social Science Faculty Teams for endorsing the study. This work was supported by the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (grant numbers EP/J005959/1 and EP/J005231/1).

References

- Braun, V. and Clarke, V. (2006) ‘Using thematic analysis in psychology’, Qualitative Research in Psychology, vol. 3, pp. 77-101.

- Bruning, R., Dempsey, M., Kauffman, D. F., and McKim, C. (2013) ‘Examining dimensions of self-efficacy for writing’, Journal of Educational Psychology, vol. 105, no. 1, pp. 25-38.

- Chandrasegaran, A., Ellis, M. and Poedjosoedarmo, G. (2005) ‘Essay Assist—Developing software for writing skills improvement in partnership with students’, Regional Language Centre Journal, vol. 36, no. 2, pp. 137-155.

- Krueger, R. A. (1994) Focus Groups: A Practical Guide for Applied Research, 2nd ed., Thousand Oaks, CA, Sage Publications.

- Morgan, D. L. (1988) Focus Groups as Qualitative Research, Series 16, Newbury Park, CA, Sage Publications.

- Roscoe, R. D., Varner, L. K., Weston, J. L., Crossley, S. A. and McNamara, D. S. (in press) ‘The Writing Pal Intelligent Tutoring System: Usability Testing and Development’, Computers and Composition. Available online: http://129.219.222.66/pdf/Roscoe2012WritingPalTutor.pdf (accessed 14 April 2013).

- Tickle, L. (2011) ‘Essay-writing trips up students’, The Guardian, 26 April. Available online: http://www.guardian.co.uk/education/2011/apr/26/students-essay-writing (accessed on 14 April 2013).

- Van Labeke, N., Whitelock, D., Field, D., Pulman, S. and Richardson, J.T.E. (2013a) ‘OpenEssayist: extractive summarisation and formative assessment of free-text essays’, Proceedings of the 1st International Workshop on Discourse-Centric Learning Analytics, Leuven, Belgium, April 2013.

- Van Labeke, N., Whitelock, D., Field, D., Pulman, S. and Richardson, J.T.E. (2013b) ‘What is my essay really saying? Using extractive summarization to motivate reflection and redrafting’, Proceedings of the AIED Workshop on Formative Feedback in Interactive Learning Environments (Memphis, TN, Jul. 2013).

- Whitelock, D. (2010) ‘Activating assessment for learning: Are we on the way with Web 2.0?’ in Lee, M. J. W. and McLoughlin, C. (eds.) Web 2.0-Based E-Learning: Applying Social Informatics for Tertiary Teaching, Hershey, PA, IGI Global, pp. 319-342.