Searching for 'People like me' in a Lifelong Learning System

N. Van Labeke , G. Magoulas , A. Poulovassilis

Abstract

The L4All system allows learners to record and share learning pathways through educational offerings, with the aim of facilitating progression from Secondary Education, through to Further Education and on to Higher Education. It provides facilities for learners to create, maintain and share their own 'timeline' (a chronological record of their learning, work and personal episodes) with other users, in order to foster collaborative elaboration of future goals and aspirations. This paper describes the design of the system's personalised mechanism for searching for 'people like me', presents the results from an evaluation session held with a group of mature learners, and identifies recommendations arising from this evaluation which have led to further development of the system.

1 Introduction

Supporting the needs of lifelong learners is increasingly at the core of learning and teaching strategies of Higher Education and Further Education institutions and poses a host of new challenges. In particular, face-to-face careers guidance and support has been found to be uneven [1], leading some to consider the role of online support in providing some form of careers guidance [2,3]. Communication and collaboration tools provide new opportunities for exploring the role that social networks and factors play in making career decisions, and for supporting educational choices [4]. The need for better support for lifelong learners, the patchy provision of careers and educational guidance at critical points, and the potential of ICT to support these needs provided the rationale that underpinned the development of the L4All system. We refer the reader to [5] for details of the aims, research and development methodology, technical approach and evaluation of the original system.

In brief, the L4All system aims to support lifelong learners in exploring learning opportunities and in planning and reflecting on their learning. It allows learners to create and maintain a chronological record of their learning, work and personal episodes – their timeline. Learners can share their timelines with other learners, with the aim of encouraging collaborative formulation of future learning goals and aspirations. The focus is particularly on those post-16 learners who traditionally have not participated in higher education. Among this group, social factors are found to have a significant influence on educational choices and career decisions [5].

The L4All user interface provides screens for the entry of personal details, for creating and maintaining a timeline of past and future learning, work and personal episodes, and for searching over courses and timelines made available by other users, based on a variety of search criteria. This paper describes the design of a new facility which supports personalised searching for timelines of “people like me” (Section 2), summarises the results of an evaluation session held with a group of mature learners (Section 3), and discusses outcomes arising from this evaluation (Section 4).

2 Search for Timelines of “People Like Me”

The initial prototype of the L4All system supported several search functionalities over users and their timelines. However, searching over timelines returned matches based solely on the occurrence of specified keywords in one or more episodes of the timeline and did not exploit the structure of the timeline; also, the search results were not personalised to the user performing the search. An alternative approach was needed that could take into account both these issues i.e. some form of comparison between a user’s own timeline and the other timelines in the L4All repository.

Similarity metrics offer such a possibility. They have been widely used in information integration and in applied computer science [6,7]. In Intelligent Tutoring Systems, they have been used to compare alternative sequences of instructional activities produced by authors [8]. In our context, our starting point was to encode the episodes of a timeline into a token-based string, and we refer the reader to [9] for details of our encoding method. We also report in [9] on a comparison of ten different similarity metrics that we considered for trialling in the system. For the version of the system that we evaluated as discussed below, four of the metrics were deployed: Jaccard Similarity, Dice Similarity, Euclidean Distance, NeedlemanWunch Distance – see www.dcs.shef.ac.uk/~sam/stringmetrics.html. These are identified as Rule1 – Rule 4, respectively, together with a brief description, in the user interface.

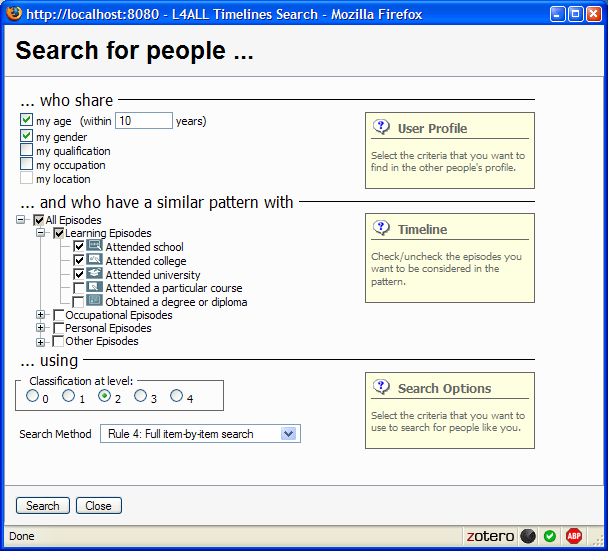

A dedicated interface for the new search for “people like me” facility was designed, providing users with a three-step process for specifying their own definition of “people like me” – see Figure 1. In the first step, the user specifies those attributes of their own profile that should be matched with other users’ profiles; this acts as a filter of possible candidates before applying the timeline similarity comparison. In the second step, the user specifies which parts of the timelines should be taken into account for the similarity comparison, by selecting the required categories of episode (there are several categories of episode; some categories of episode are annotated with a primary and possibly a secondary classification, drawn from standard U.K. occupational and educational taxonomies). In the final step, the user specifies the similarity measure to be applied, by selecting the “depth” of episode classification to be considered by the system and the search method i.e. one of Rules 1-4 above.

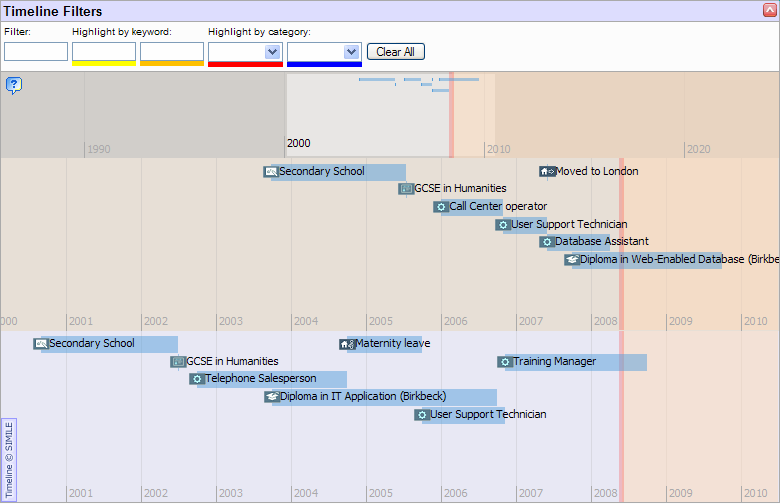

Once the user’s definition of “people like me” has been specified, the system returns a list of all the candidate timelines, ranked by their normalised similarity. The user can select one of these timelines to visualise in detail, and the selected timeline is shown in the main page as an extra strip below the user’s own timeline (see Figure 2).

Figure 2

Displaying the user’s timeline with another user's timeline.

The two timelines can be synchronised by date, at the user’s choice. Episodes within the selected timeline that have been designated as being public by its owner are visible, and the user can select these and explore their details.

3 Evaluation

The aim of this first design of a personalised search for “people like me” was to gather information about usage and expectation from users of such functionality. An evaluation session was undertaken with a group of mature learners on the Certificate in IT Applications at Birkbeck College, organised around three activities.

Activity 1 was a usability study of the extended system, focusing on participants building their own timelines and exploring also other aspects of the system. Activity 2 was an evaluation of the new searching for “people like me” functionality, focusing on participants exploring different combinations of search parameters and reporting on the usefulness of the results returned by the system. Activity 3 was a postevaluation questionnaire and discussion session. We refer the reader to [10] for details of these activities. Activity 2 in particular required a significant amount of preparatory work, due to the need for an appropriate database of timelines to search over. Which profile and timeline participants would use was also an issue. The best option would have been for users to have maximum familiarity with their profile and timeline, and therefore to use the profile and timeline they had created during Activity 1. However, since we did not know in advance what would be the participants’ profiles and timelines, it would have been difficult to build an appropriate database of “similar” timelines for supporting Activity 2. We therefore opted for an artificial solution: providing participants with an avatar, i.e. a ready-to-use artificial identity, complete with its own profile and timeline, and generating beforehand a database of other timelines based on various degrees of similarity with these avatars.

Of the 10 people who had agreed to participate in the evaluation session, 9 people came on the day, and we refer to them as bbk1-bbk9 below. They represented a variety of learners in terms of their experience and background, as extracted (after the session) from their profile and timeline data recorded within the L4All system: gender 3 female and 6 male; age 1 in 20’s, 3 in 30’s, 4 in 40’s, 1 in 50’s; and background with a mean of 3 educational episodes (SD 1.7), 2.75 occupational episodes (SD 2.0) and 2.1 personal episodes (SD 1.2).

Activity 1 indicated overall satisfaction of this group with the main functionalities of the system. It also identified a number of usability issues ranging from low-level interface inconsistencies (improper labels, lack of contextual help) to more high-level usage obstacles (difficulty of first-time access to the system), most of which have now been addressed.

However, Activity 2 did not fulfil our expectations of identifying user-centred definitions of “people like me”. Most participants took this activity at face value, selecting some parameters, exploring one or two of the timelines returned, and starting again. They could see no reason to try different combinations of search parameters, as their first try was returning relevant results.

The participants’ responses on searching for “people like me” in the self-report forms were 58% Poor/Mostly Poor. Participants could not see the benefits of this functionality: "you need to convey the benefit of finding people with similar timelines; this is CRUCIAL: what does it tell me if I find someone who is like me, based on criteria provided? Can I conclude anything from this? Need to create a set of examples to demonstrate how this timeline comparison is useful" – bbk3.

Two factors seem to have had a negative impact on the outcome of this activity: the artificialness of the database used for the search (not enough variability in the timelines generated) and difficulties in grasping the meaning of some of the search parameters, notably the classification level and the search method ("search methods – rule 1-4 – are not clear"; "level of classification not clear at all" – bbk1, bbk3, bbk4).

However, during the subsequent discussion in Activity 3, it became apparent that participants could appreciate what this functionality could deliver if it were applied in a real context: "search needs to be based on aspiration/wish" – bbk4.

Moreover, the post-evaluation question on the search for “people like me” functionality had only 8% of Poor/Mostly Poor, seeming to contradict participants’ experience while actually doing this task. This contradiction may be explained by the difference between reporting on the task on the spot, and answering a post-evaluation questionnaire after participants have had time to reflect on the task. This was also illustrated by the discussion at the end of the session, in which participants identified the potential of searching “for people like me” despite the usage difficulties.

4 Outcomes and Concluding Remarks

Lifelong learners need to be supported in reflecting on their learning and in formulating their future goals and aspirations. In this paper we have described a facility for searching for “people like me” as part of a system that aims to support the planning of lifelong learning. The aim of this first design of a personalised search for “people like me” was to gather information from users about their potential usage and expectation from such functionality, and we have reported here on the results of an evaluation session held with a group of mature learners.

A critical issue highlighted by evaluation participants is the question of providing learners with support for exploiting the results of a similarity search. In this paper we have reported on a purely visualisation approach, which is based on displaying the user’s own timeline together with a timeline selected by the user from those returned by the search. A specifically designed dynamic widget allows the user to scroll backwards and forwards across each timeline and to access individual episodes.

Such an interactive visualisation of timelines certainly helps users to explore different timelines and episodes, but more proactive supports are also required. In particular, users need to be able to identify the reasons for the system deeming two timelines as being similar. Metrics such as Needleman-Wunsch in fact do offer the possibility for such identification, by enabling backtracking of the similarity computation and showing the alignments of the sequences of tokens i.e. the alignments between pairs of episodes in the two timelines. This opens up the possibility for more contextualised usage of timeline similarity matching, which explicitly identifies possible future learning and professional possibilities for the user by indicating which episodes of the target timeline have no match within the user’s own timeline and therefore potentially represent episodes that the user may be inspired to explore or may even consider for their own future personal development. We will discuss such a contextualised usage, and its evaluation with two groups of mature learners, in a forthcoming paper.

Acknowledgments.

This work was undertaken as part of the MyPlan project, funded by the JISC Capital e-Learning programme.

References

- Bimrose, J., Hughes, D.: IAG Provision and Higher Education. IAG Review: Research and Analysis Phase. Briefing Paper for DfES. University of Warwick (2006)

- Cogoi, C. (ed.): Using ICT in Guidance: Practitioner Competencies and Training. Report of an EC Leonardo project on ICT Skills for Guidance Counsellors. Outline Edizone, Bologna (2005)

- Cych, L.: ‘Social Networks’ in Emerging Technologies for Learning. Coventry. Becta, 32– 40 (2006)

- de Freitas, S., Yapp, C. (eds.): Personalizing Learning in the 21st Century. Network Continuum Press, Stafford (2005)

- de Freitas, S., Harrison, I., Magoulas, G.D., Mee, A., Mohamad, F., Oliver, M., Papamarkos, G., Poulovassilis, A.: The development of a system for supporting the lifelong learner. British Journal of Educational Technology 37(6), 867–880 (2006)

- Cohen, W.W., Ravikumar, P., Fienberg, S.E.: A comparison of string distance metrics for name-matching tasks. In: Proc. IIWeb 2003 – Workshop on Information Integration on the Web, at IJCAI 2003, pp. 73–78 (2003)

- Gusfield, D.: Algorithms on Strings, Trees, and Sequences. Computer Science and Computational Biology. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (1997)

- Ainsworth, S.E., Clarke, D.D., Gaizauskas, R.J.: Using edit distance algorithms to compare alternative approaches to ITS authoring. In: Cerri, S.A., Gouardéres, G., Paraguaçu, F. (eds.) ITS 2002. LNCS, vol. 2363, pp. 873–882. Springer, Heidelberg (2002)

- Van Labeke, N., Poulovassilis, A., Magoulas, G.D.: Using Similarity Metrics for Matching Lifelong Learners. In: Woolf, B.P., Aïmeur, E., Nkambou, R., Lajoie, S. (eds.) ITS 2008. LNCS, vol. 5091, pp. 142–151. Springer, Heidelberg (2008)

- Van Labeke, N.: Preliminary Evaluation Report, MyPlan Project Deliverable 5.1 (August 2008), http://www.lkl.ac.uk/research/myplan/